we are going to get through

Of all the dualities constantly rattling around in my brain – form and content, structure and agency, ideal and material – the tension between individual and collective feels among the most foundational, the most likely to cast its shadow over conversation and filter the ways I’m weighing things. We can’t help but believe ourselves autonomous, but of course that’s little more than a trick of the light. Freedom is at best a stubborn aspiration, something towards which we reach, knowing that it’s only in death that we step out of the web of interconnectedness that constitutes life on Earth. While we’re here, we’re unavoidably tethered to living surroundings, ultimately dependent on others; you don’t need to be a Marxist to know that individual existence is only possible under the aegis of the collective, and that that’s actually quite a beautiful thing.

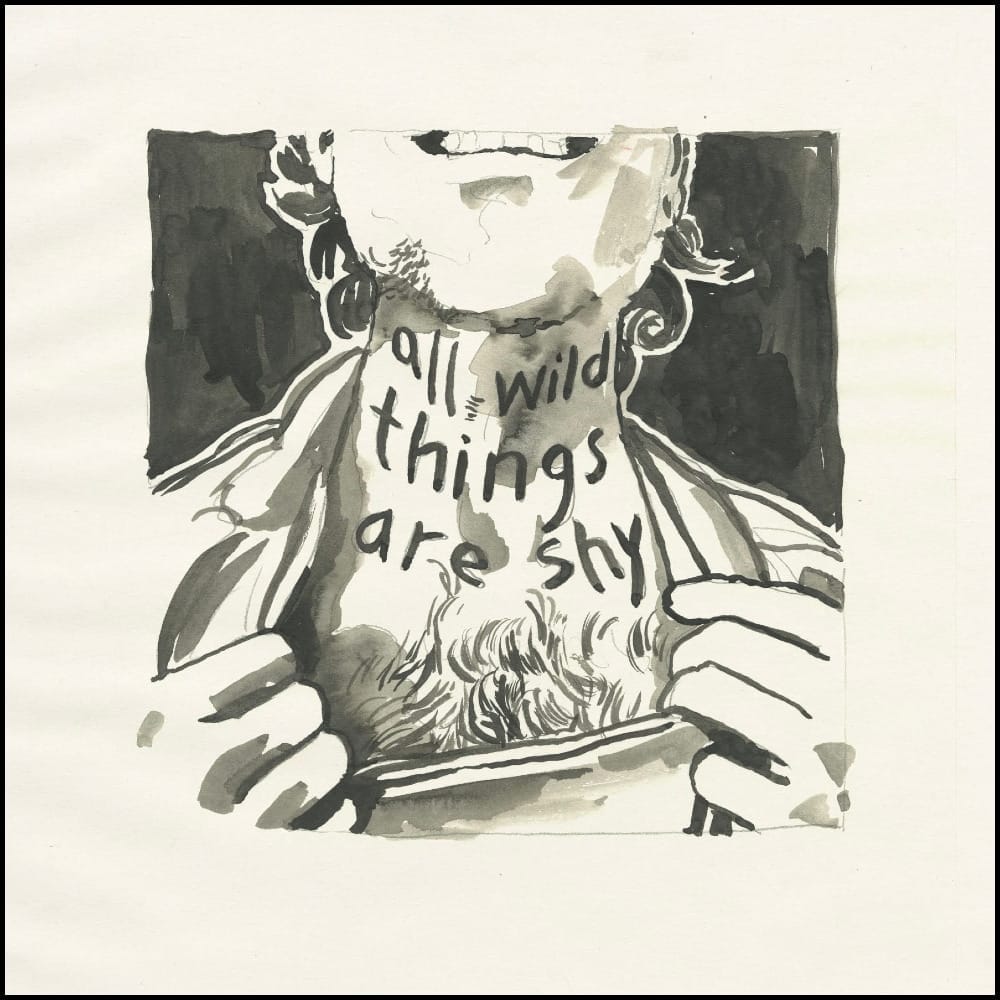

I never got to meet Richard Laviolette, but when I learned of his passing in September of 2023, I felt touched by the loss in a way I’m still not sure how to faithfully describe. Friend of friends and southern Ontarian DIY luminary, comrade-in-waiting and fellow traveller, nurturer of the kind of community most of us would feel lucky to imagine ourselves a part of, Richard spent the better part of two decades sharing scrappy, passionate indie-folk, punk as hell in all the ways that matter. “Richard’s work is a tapestry of grief and wonder,” writes Niko Stratis, “all the beautiful and hard parts of a life held together with tender thread.” This past Fall, You’ve Changed Records released All Wild Things Are Shy, his final album and a gracefully staggering document, a purposeful and tenderly imperfect monument to a life’s worth of living these ethics: it’s at once a crystal-clear articulation of a singular voice and a cooperative happening that could only have been achieved thanks to a bones-deep commitment to the joy of collectivity.

It’s a record that’s aware of and reverent towards its influences without being caged by them. Plenty of touchstones warrant reference: I’m reminded of the simplicity and directness of a Nina Nastasia, the anecdotal specificity of a John K. Sampson, the understated wisdom of a Townes Van Zandt, the dark humour of a Vic Chesnutt. True to its primary form, straight-forward song structures and familiar melodic themes are vehicles for big truths, come by honestly and conveyed with humility. Among the broader narrative strokes, Richard deploys everyman country-rock tropes with an arch intentionality that wards off any sense of cliché: “Everyone needs to not feel old/ Everyone needs a little rock and roll.” There’s little that’s ostentatious or showy about the songs collected here: though arranged with generosity and warmth, the compositions have an economy at their core, each song animated by a steadfast communicative imperative.

Richard wrote and recorded the album with the end of his life in sight, and that dark weight is all over it, though it’s never maudlin or self-pitying. There’s not a lot of rage, but neither is there surrender. If there’s a world-weariness, it’s illustrated in relief, in staunch refusal of the cynicism always muddying our ankles; if there’s an overarching sentiment it’s rather one of affirmation, a driving insistence that we double down on the things we care about – including ebullience and levity. The quotidian and the existential are faced here with equal resolve – “With tea pots and secret hideouts/ And three books that I hold dear/ There are some records you can only listen to/ At this time of year” – and what emerges is a vision of a bleak world seen through warm, wide eyes. “Train of Death” names its subject bluntly, but its choral refrain – “I can feel it in my heart get closer every day” – has such a raucous lilt to it, it’s as though, brought together by looming tragedy, these are dear friends exactly where they ought to be. “Saved by Rock and Roll,” the album’s centrepiece and likely its most bracing passage, is perhaps the clearest expression of what’s at stake here, the urgency of it clearly audible in the straining, clipped delivery of Richard’s vocal lines. In a way the song brings to mind those early Against Me! demos, valourizing the work we do to generate meaning through sheer force of will, in spite of the knowledge that, of course, none of us will be saved.

Indeed, there’s a workmanlike quality to All Wild Things Are Shy, though it’s not because there’s a lot of direct mention of work as such, but because there’s a way labour is made visible and tactile here, labour as collective actualization and as individual becoming. You can feel the strain of muscles moving around gear, almost taste the whole becoming more than a sum of parts. The record is a labouring of love, in love, for love, against the things that threaten to crush us – the finality of a death, the intoxicating allure of hopelessness and nihilism. In this way it almost reads like a manifesto: change need not mean defeat, acceptance need not mean resignation. And yes, what we’re doing here matters.